[At one point I swore I’d ignore this movie, and here I am writing more than five thousand words about it. Well, life has far worse surprises in store.

Departing from my usual practice (and dangling a participle), this is essentially a first draft. As Pascal is supposed to have said, or would have said if he’d had a blog, I didn’t have time to write a shorter series of posts.

Oxfordians, please feel free to comment; as I’ve said, I will not suppress or edit you in any way for the expression of your views, though I’ll do so for the usual reasons—personal attacks and the like. Please don’t abuse the privilege by being anything less than civil. Please also note that I am not going to respond to any comments on these posts. They contain everything I have to say on the subject of this movie. Let the games begin.]

[F]or me there was an incredible script that I bought eight years ago. It was [initially] called Soul of the Age which pretty much is the heart of the movie still. It’s three characters. It’s like Ben Jonson, who was a playwright then. William Shakespeare who was an actor. It’s like the 17th Earl of Oxford who is the true author of all these plays. We see how, through these three people, it happens that all of these plays get credited to Shakespeare. I kind of found it as too much like Amadeus to me. It was about jealousy, about genius against end, so I proposed to make this a movie about political things, which is about succession. Succession, the monarchy, was absolute monarchy, and the most important political thing was who would be the next King. Then we incorporated that idea into that story line. It has all the elements of a Shakespeare play. It’s about Kings, Queens, and Princes. It’s about illegitimate children, it’s about incest, it’s about all of these elements which Shakespeare plays have. And it’s overall a tragedy. That was the way and I’m really excited to make this movie.

—Roland Emmerich, interview quoted in Wikipedia.

It’s finally here. Nemesis has struck. Anonymous, the movie Sir Derek Jacobi suggests will “obviously” make all “orthodox Stratfordians” “apoplectic with rage,” had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. I guess I count as one of those orthodox Stratfordians, but having seen the movie on Saturday morning, September 17, I write more in sorrow than in anger. I feel sorry for Oxfordians, who seem to be under the impression that Emmerich had some interest in arguing for their cause; in fact he is only interested in getting people to pay to see his movie. I want to make that point while giving the movie the fairest run I possibly can, so let’s start with the straightest, most neutral plot summary I can manage. If you’re averse to plot summary, or a plot summary of this particular movie, skip directly to the next post; this one goes on for quite a while.

Fair warning, too: pretty much everything that follows is a spoiler.

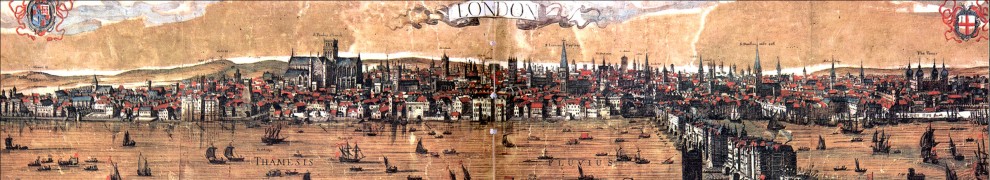

We open with—of all things—an overhead shot of a contemporary city; I assume it’s either New York or London. We pan down to Sir Derek getting out of a cab and entering a theatre whose marquee reads “ANONYMOUS.” The stagehands are relieved; he’s evidently late. The curtain opens immediately and he launches into a prologue stating the basic Oxfordian position. Meanwhile actors are seen backstage, preparing for the roles they will shortly be playing in the film proper.

We segue via an actor running into the film proper, chased by those troops. He turns out to be Ben Jonson, and the troops are in the employ of the royal adviser and spymaster Robert Cecil. Jonson is flushed out of his hiding place under the stage of the Globe when the troops torch it, and he’s brought to Cecil, who’s ready to have him tortured to find out where “de Vere’s plays” are.

We flash back five years earlier (since the preceding scene occurs right after Oxford’s death in 1604, this must be 1599); Jonson gets arrested again, as his play is halted by the censors at the Globe. Christopher Marlowe, in the audience, mocks him.Oxford has been brought to the theatre by the Earl of Southampton; later he officiates at a tennis match between Southampton and the Earl of Essex during which they ask for his help in a conspiracy to install James of Scotland as Elizabeth’s successor; noncommittally, he suggests that words such as they saw on the stage are real power.

Later at court, Oxford presents a play for the Queen; it’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and we flash back again, this time forty years, to a production of the same play for the young Queen. The author is the nine-year-old boy playing Puck—who turns out to be Oxford.

We have three time streams now and we’re going to move back and forth between them for the rest of the movie. That can get terribly confusing, a bad thing in a putative blockbuster, as Emmerich ought to know. If I can’t figure out when something is happening until I look back at my ten pages of notes, the punters are going to be lost. So I’m going to try to tell the rest of the tale chronologically.

So: after his childhood triumph, we next see Oxfordentering into the household of William Cecil, Elizabeth’s paramount adviser; if you remember the movie Elizabeth, he was played by Richard Attenborough. He’s to be educated as a gentleman there but is not to write poetry in this Puritan household. Of course, he disobeys this stricture, and kills a servant who spied on him by stabbing him behind an arras—a somewhat too blatant allusion to Hamlet. (Incidentally, it’s to Emmerich’s credit that he portrays Oxford as the arrogant aristocratic little shit he seems to have been in real life; the character is not sympathetic at all. The movie doesn’t explore Oxford’s alleged homosexuality, but then most movies about the author of Shakespeare’s plays don’t, do they now?) Cecil will hush it up and save Oxford’s head from the block on condition that he never write any more poetry and that he marry his daughter.

At some later point Oxford has returned from his European travels and has already produced Henry V and Romeo and Juliet. It’s the latter production that enables the Queen to guess that he is the author (for the moment she seems to have forgotten her praise of his nine-year-old effort), and he gets her into bed for it. (This is confusing, since it’s only in the 1599 story that Oxford asks Ben Jonson to front for him, and the Queen is young, so this can’t be 1599.) The next morning, in what seems to be Emmerich’s version of the Aubade in Romeo and Juliet, the Queen asks him: “Are you Prince Hal or Romeo?” and answers herself: “You’re Puck,” indicating that she does remember. Naked, he recites “O Mistress Mine,” one of Feste’s songs from Twelfth Night, and she goes down on him. (Yes, that’s clearly implied.)

Somewhat later, Cecil berates Oxford about the fact that he’s impregnated the Queen; she’ll have to go on tour, have the baby somewhere private, and give it up, while Oxford must give up writing poetry. To spoil even this exposition, the child will turn out to be the Earl of Southampton.

With all the cross-cutting and fudged chronology it’s hard to tell, but I think the rest of the movie, except for its final scenes, takes place in 1599. There’s one crucial scene I can’t quite place from my notes. At some point, somehow Oxford’s plays are in favor again, and Hamlet is presented at court. The actor playing Polonius is dressed and bearded identically to Cecil, so that there’s no mistaking who the busybody stabbed behind the arras (remember the servant Oxford murdered?) is supposed to be. Cecil naturally now really wants Oxford dead, and bribes his fencing master to do the deed, but Oxford kills him instead; though the fencing master’s blade isn’t said to be poisoned, another obvious allusion to Hamlet. It’s the mature Oxford in this swordfight, but I frankly can’t trace how the movie got there; if anybody can, please do so in the comments.

Anyway: to pick up the thread, let’s go back to Jonson, released from his first imprisonment. He finds himself ferried across the Thames and brought to a mansion. Oxford has summoned him to make him an offer: to stage the many, many plays Oxford has written, under his, Jonson’s name. Jonson takes back Henry V for consideration. Though sworn to secrecy, he does discuss the proposition with the nearly imbecilic actor Will Shakespeare.

Then there’s a cut to the Cecils, old William and hunchbacked young Robert, complaining that Oxford is back staging plays again and determining that they need to get Essex shipped off to Ireland; the malleable, at this point nearly senile Queen is easily made to agree.

Henry V is a huge success, despite Marlowe’s sarcasm, and amid cries of “Author!” (do we note a theme developing?), out of nowhere Shakespeare bursts onto the stage. Oxford, in the audience, is enraged and later takes it out on poor Jonson, who rejected the deal, he says, because “These plays aren’t in my voice.” to which Oxford responds in a fury, “You have no voice! That’s why I chose you.” That’s a rather cruel judgment on Jonson, but it ties in to the only scene where we get some explanation of why Oxford writes. In an angry exchange with his wife (”You’re writing again! After you swore not to!”), he says that he hears voices (“The voices, I can’t stop them”) that he can only silence by writing down what they say. Why he then has to have those writings performed is a whole other issue he doesn’t address, but there you have the explanation of the genius of “Shakespeare.”

Meanwhile, what about the idiot actor Shakespeare? He’s enjoying such a popular triumph in Henry V that he goes crowdsurfing. Yes, Shakespeare may not have written his plays, but he invented crowdsurfing—take that, Courtney Love. Christopher Marlowe, inflamed by jealousy, betrays Shakespeare to the Master of the Revels. This is the only conscious irony I discerned in the whole movie; that Marlowe, himself a claimant to the mantle of “Shakespeare” according to some, should claim that Shakespeare was somebody else’s beard. He soon pays the price, though; he’s found dead in a tunnel.

Soon thereafter, Shakespeare the idiot actor, wearing a ludicrous false beard and nose (no doubt he’d have worn Groucho glasses if they had been invented), crosses the Thames to extort Oxford, saying “My expenses have aggrandized,” a comic misuse meant to underline his stupidity. He gets his money and his plays, though he is humiliated by Jonson, who exposes his inability to write in front of the crowd of writers at the Mermaid Tavern.

Meanwhile, the political plot is heating up. Essex is recalled from Ireland and surprises the Queen in her boudoir; she isn’t made up and we get a glimpse of her as a hideous hag. We know from this that Essex is going to die, just as Actaeon did when he saw Diana (though the goddess was divinely beautiful, the invasion of privacy is what matters). Oxford now promises to intervene for the disconsolate Essex, by giving the Queen a book that will impel her to invite him for an interview where he will plead for Essex. That book is Venus and Adonis. But that’s not the only help Oxford has to offer; he gives Richard III to Shakespeare and somebody pays for a single command performance.

Back at the Globe, Jonson learns that Shakespeare, who is now a shareholder in the theatre, has interdicted him forever; in retaliation, Jonson betrays the plan to produce Richard III to the Master of the Revels. At the performance, the hunchbacked Richard is dressed and bearded like the hunchbacked Robert Cecil. The groundlings boo him, cheer for Essex, and take to the streets, but are halted by cannon in the middle of London Bridge.

Meanwhile Essex has touched off the piece of tomfoolery we know as the Essex Rebellion of 1601; he’s trapped, with Southampton, in a palace courtyard, where his men are shot to bits. Oxford watches from a window while he waits to see the Queen. Instead, Robert Cecil emerges from the shadows, like a mad scientist’s henchman, to deliver shocking new revelations. The bastard son of the Queen whose identity had been an issue is—Oxford himself. He’s thus not only Southampton’s father, he is his half-brother. Old Cecil, his son explains, had planned it all to make Oxford king and his, Cecil’s, grandson his successor (explaining the coerced marriage to Cecil’s daughter)—and he blew it to write poetry.

Essex is beheaded but Southampton is spared; the Queen had no compunction about executing her own son but stayed her hand for his father, Oxford’s sake. In a final meeting, she exacts her price from Oxford: “None of your plays will ever carry your name.” not long after, Elizabeth dies and we see James I crowned. At some point after that, Jonson, drunk and tossed out of the Globe, visits Oxford, who is dying. Oxford asks Jonson what he thinks of his writing, and Jonson calls him the “soul of the age.” Oxford gives him his remaining manuscripts, including King Lear, and enjoins him to keep them safe from the Cecils. Jonson asks why Oxford would entrust him with these precious documents—after all, he betrayed him—to which Oxford responds: “You may have betrayed me. But you can never betray my words.”Oxford’s wife—a Cecil, remember—sees Jonson leave with the manuscripts, and we’re back to the opening scene where Jonson was captured and threatened with torture. Cecil is apparently satisfied with his explanation that the manuscripts burned when they torched the theatre and releases Jonson, who returns to the smoking ruins to find the plays scorched but sound.

Meanwhile, James I delights in seeing a play at court, turning to Robert Cecil with the wish that he’ll see many more—especially by that fellow Shakespeare, whose work he’d seen in Edinburgh.

Sir Derek returns to deliver a short epilogue. And that’s it.

Well, there’s the story. I’ve gone on to the tune of about 2300 words not just because I had ten pages of notes to use up but because I wanted to present the story in detail and straight. I’ve tried, not entirely successfully, to resist all opportunities for fact checking or snark; believe me, there’ve been many, and I’ll succumb in the next post.